The Dangers of “Good” Posture

Conventional “wisdom” can really fuck up a body. Exhibit A, ladies and gentlemen, are traditionally-shaped cloud-like shoes that are believed to be healthy and supportive. Few ideas are as simple and yet fundamentally problematic as the traditions of “good posture.” When athletes walk into Apiros (with pain) and demonstrate this idea of good posture, it’s the first thing I tell them to stop doing. It's almost always women, and they’re usually making things worse.

Are you surprised? What do you think of when I mention “good posture”? Are you reminded of your teacher or parent who lambasted you to sit up straight when at your desk or dinner table? Maybe you’re reminded of the articles floating around health and wellness blogs about spinal curvature and the disastrous effects of bad posture or cell phone overuse. (Like this one. Come on, Harvard. Or this one from the Mayo Clinic.) Or maybe you’re worried you’re going to look fat in photos if you don’t suck your belly in. Or maybe you’re starting to wonder why your back still hurts despite believing you have fantastic posture.

Improving posture is well-intentioned and deeply ingrained in society, but our conventional ideas of it do more harm than good. Posture is misunderstood. I find that when it comes to athletes, again, mostly women, adhering to popular principles of “good posture” hurt their bodies and careers. I’ve got a few stories for you.

“Braced Cores,” Breathing, Beauty, and HRV

One Apiros athlete is also a model. We’ll call her Stacy. She “braced” her core for photos and videos, but that contraction stayed beyond the photoshoot and throughout her day because she thought it was what you’re supposed to do. She didn't know it was causing problems. She was unaware.

As a professional endurance athlete, her breathing mechanics are paramount. Not only for her performance but also for her recovery. Maintaining “good posture” by bracing her core all the time (think belly button to spine) made her breathing more shallow and frequent. Since she took more breaths per minute than what was necessary, her commitment to “good posture” trounced her heart rate variability (HRV), worsening her ability to get into rest and digest modes, healing states. Let me explain.

Your heart rate should be variable at rest. If I measured it right now, it might look like 76, 62, 42, 79, 53…etc. That variation is partly determined by your breathing. Variable heart rates are good. When you inhale, your HR goes up. When you exhale, it goes down. The faster you breathe, the more inhales per minute you have, the lower your HRV gets. The slower you breathe, the less air you have in your lungs per minute, and the higher/better your HRV gets. Lots of variability is a good thing. Since Stacy’s breathing rate was higher than it needed to be, her HRV was suboptimal and she wasn’t recovering as well as she could. That’s a big effing deal when you’re chasing improvements that are a tenth of a percent.

I proved to her how her choices with her core affected her HRV. I have a cool device that can show HRV in real time. She watched her HRV with her “braced core” and then a relaxed stomach. The graph was drastically different and I bet you can infer which was better.

This socially conditioned stance on good “core” posture was a detriment to Stacy’s musculoskeletal system and performance, but her paycheck depended on a svelte stomach. So, I told her what I tell a lot of athletes (mostly women) about this tummy-topic, “it’s fine for your photos. Then turn it off when you’re done and return to relaxed belly-breathing.” As she learned, it’s easier said than done.

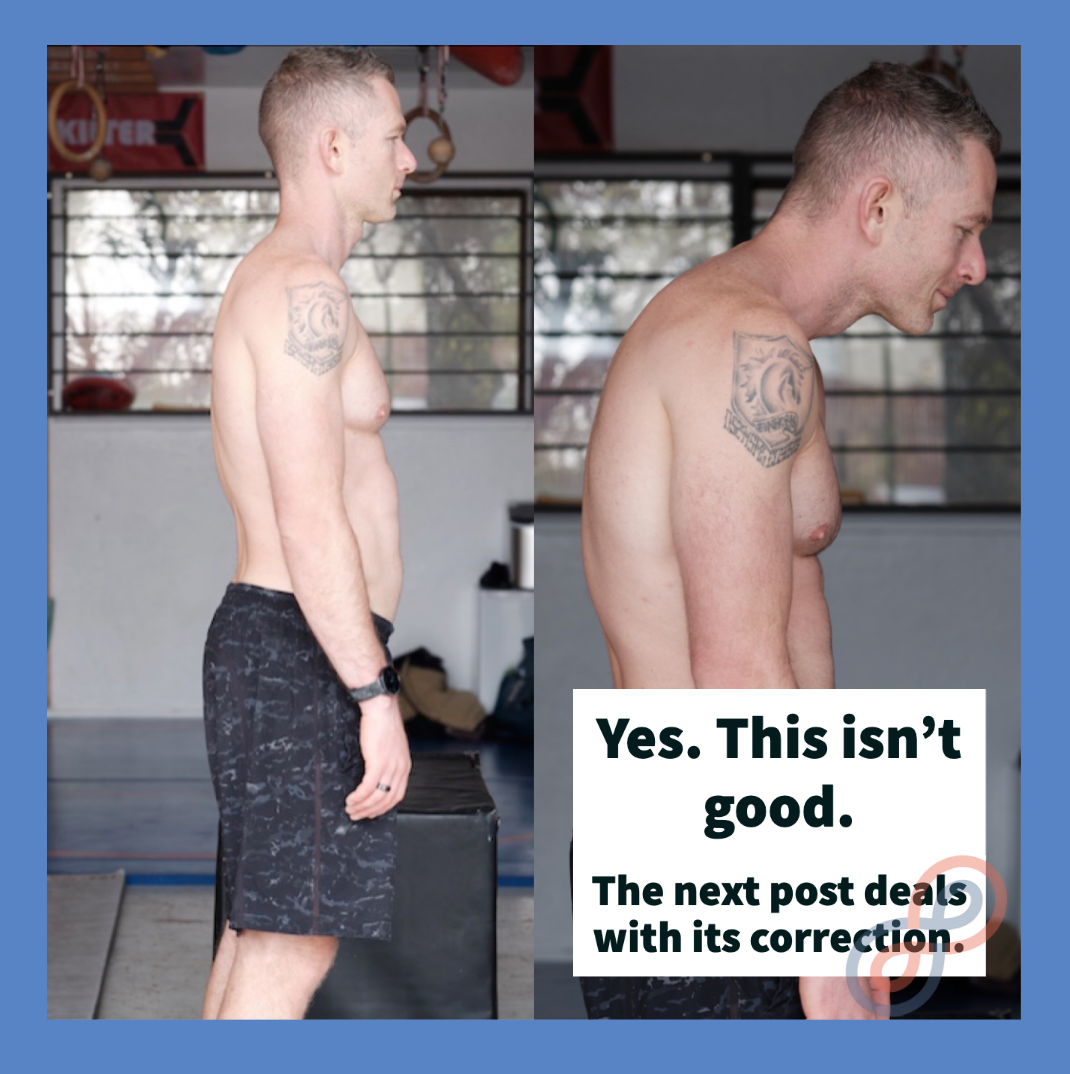

“Shoulders Back” and Sternoclavicular Joints

I’ve written at length about the importance of the sternoclavicular joint—it’s where your collarbone attaches to your sternum. It’s the sole boney joint responsible for transferring forces between the body and arms. It’s vital. And pinching your shoulder blades together all the time puts the SC joint at risk.

You see, the collarbone works (kind of) like a teeter-totter, there’s an inner end, SC joint, and an outer end, AC joint. When the outer end of the collarbone (AC) gets pulled back with pinched shoulder blades, the front of the collarbone (SC) goes forward. Do this too often for too long and your SC joint will become compromised. If that happens, then the only skeletal joint capable of transferring forces between your body and your arm is incapacitated. Your shoulder becomes entirely dependent on its muscles and tendons to transfer forces instead of any bony structure. That’s like a skyscraper being held up by its windows and scaffolding instead of its internal steel structure.

If the SC joint becomes incapacitated, forces cannot move freely through the collarbone and they are imprisoned in the shoulder. Hayley Spelman used to pinch her shoulder blades together all the time for posture and in training, and I believe that was a big cause of her tearing her supraspinatus. Forces that should have traveled along her collarbone into the rest of her skeleton were isolated to the muscles and tendons in her shoulder.

Notice the collarbones poking out at their sternums.

What Does Good Posture Look Like?

Good posture is not rigid. It’s not a single position to be in all the time. It is relaxed. It varies. It flows. It depends on the context.

In almost every facet of life, we know the human body needs and likes variability: multi-sport kids fare better than the specialized, a diverse diet and microbiome is better than strict adherence to whatever cereal Kellogg’s is currently peddling, diversification of genes is better than in-breeding, a heart rate that is variable is better than a metronome, and yet when it comes to posture and movement, the intelligentsia of movement fields preach positions and exercises that are robotic, repetitive, and monotonous. When it comes to human posture, variation is just as essential and nutritious as a colorful dinner plate.

There will be a middle ground, a neutral zone for every posture. But the middle is defined by the edges, which deserve exploration. One finds the middle ground by exploring what is within their boundaries, their capabilities. This means your workouts and postures should look different and exploratory from time to time, even if you’re a specialized athlete.

With that said, when you imagine good posture, you’re probably thinking of standing and sitting. So let’s talk about those.

Sitting Posture

If you’re in a chair, it’s likely to get work done. So, be in whatever position allows you to efficiently and effectively finish what you’re doing so you can do something else (out of the chair). If your body doesn’t feel great while seated, it has nothing to do with your posture and everything to do with what you do or don’t do away from your desk. (It might have something to do with the chair itself. Comfy chairs are great chairs.)

(Notice all the postures I assume over this sixty-minute period. I didn’t think about one of them, I’m just staying comfortable so I can write the best I can.)

Standing Posture

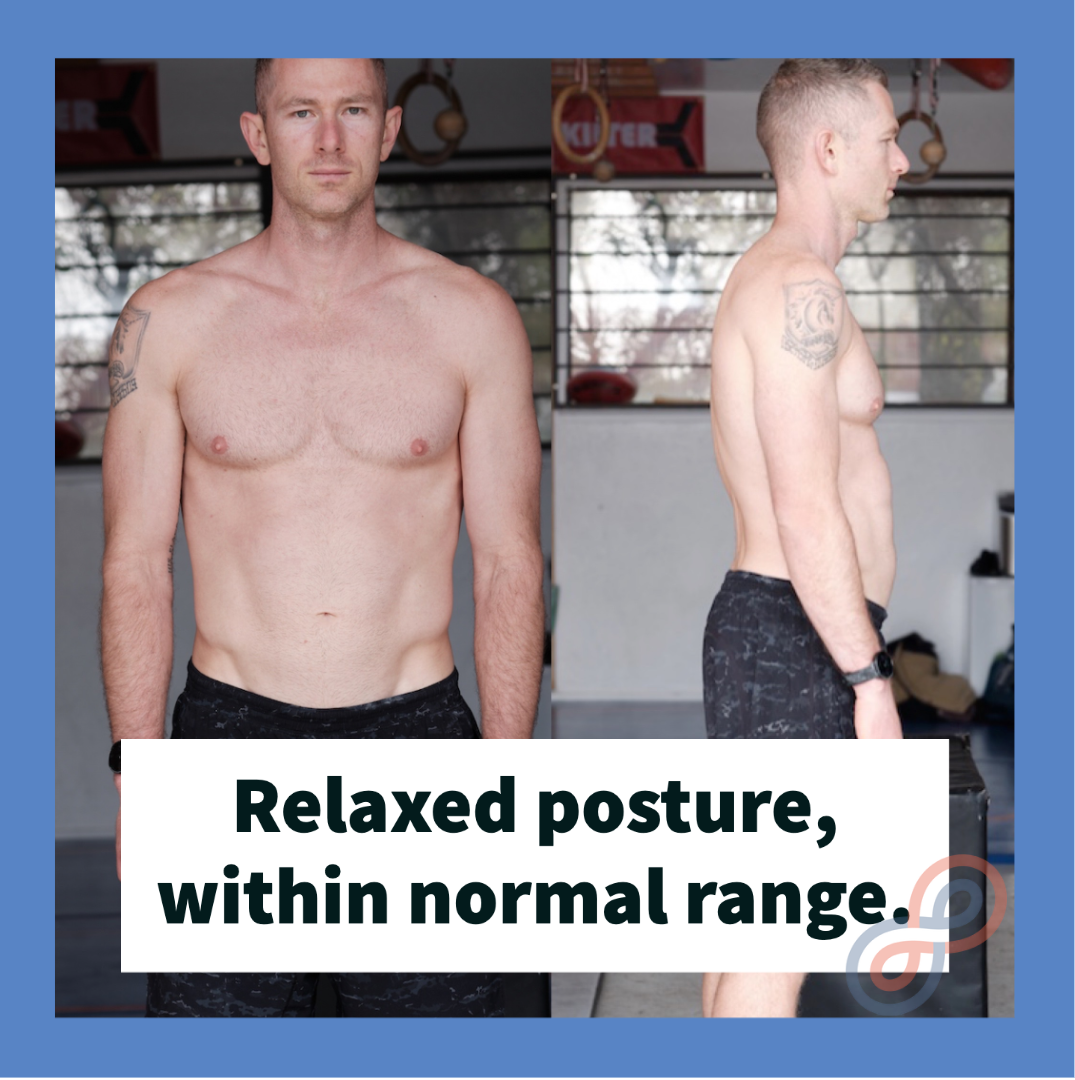

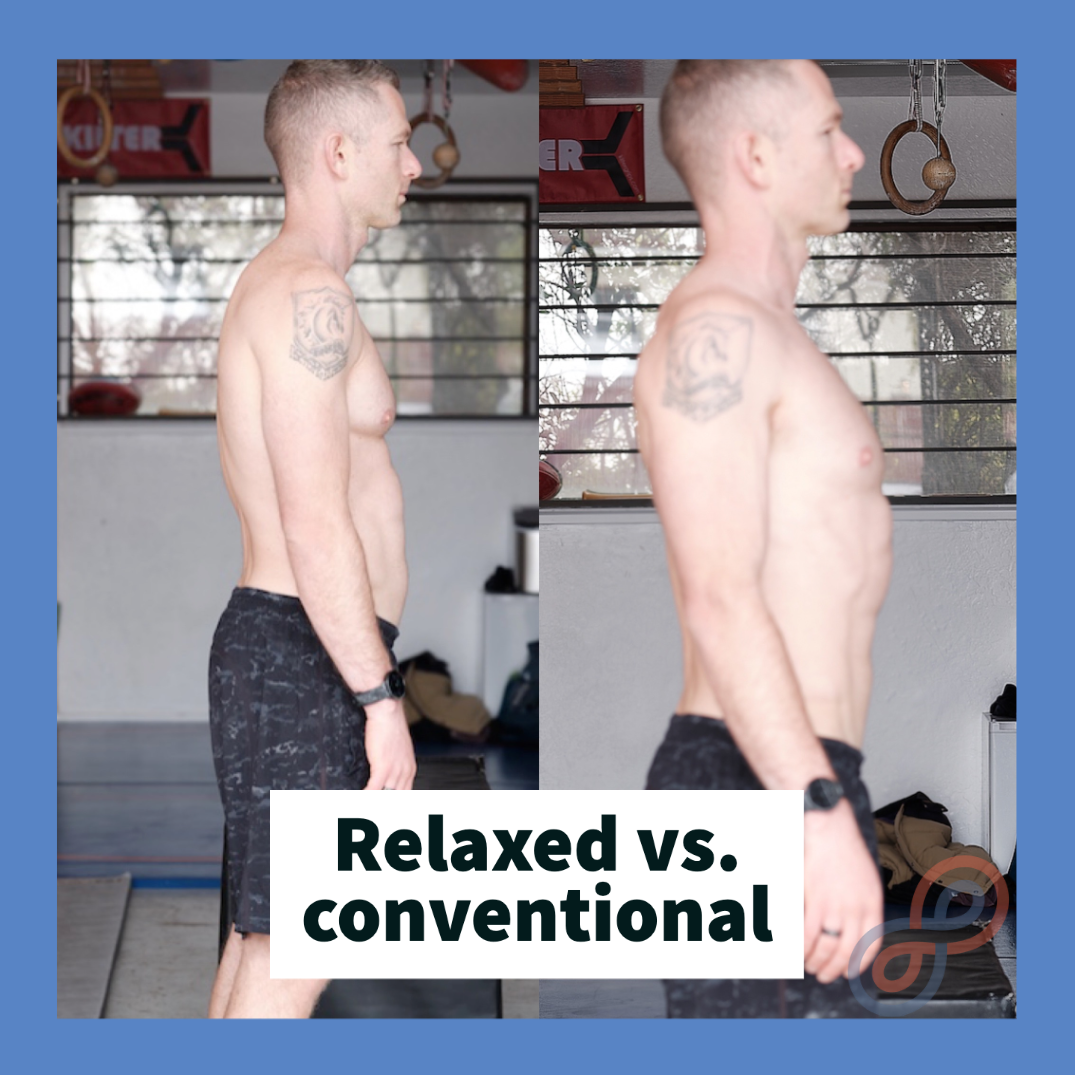

Good standing posture is relaxed posture. The stomach, shoulders, and upper back are relaxed. They are slightly round too. The stomach protrudes slightly—gasp—and the upper back rounds—double gasp! Human spines have curves! For that matter, all spines on the planet (should) have curvature. Our stomachs and shoulders need to follow those winding vertebral roads.

The amount of times I tell athletes to slouch is in the thousands, but it’s the quickest way I get them back to normal and neutral postural positions for their upper half. They walk into the gym with spines that are too upright. (Yes, such a thing exists.) My cue brings them back to somewhat normal curvature.

Standing Posture

Good standing posture is relaxed posture. The stomach, shoulders, and upper back are relaxed. They are slightly round too. The stomach protrudes slightly—gasp—and the upper back rounds—double gasp! Human spines have curves! For that matter, all spines on the planet (should) have curvature. Our stomachs and shoulders need to follow those winding vertebral roads.

The amount of times I tell athletes to slouch is in the thousands, but it’s the quickest way I get them back to normal and neutral postural positions for their upper half. They walk into the gym with spines that are too upright. (Yes, such a thing exists.) My cue brings them back to somewhat normal curvature.

Click here for my The Evolved Coach 8-Week Mentorship

Click here for In-person courses, starting in 2023.

Click here to learn about my book.